|

Dear Friends,

Long before Vermont became our 14th state, its people were known for their independence. They were not excited about joining the new United States; nor did they want to remain a part of the British crown. They liked being independent and made that clear to the other colonies on more than one occasion.

|

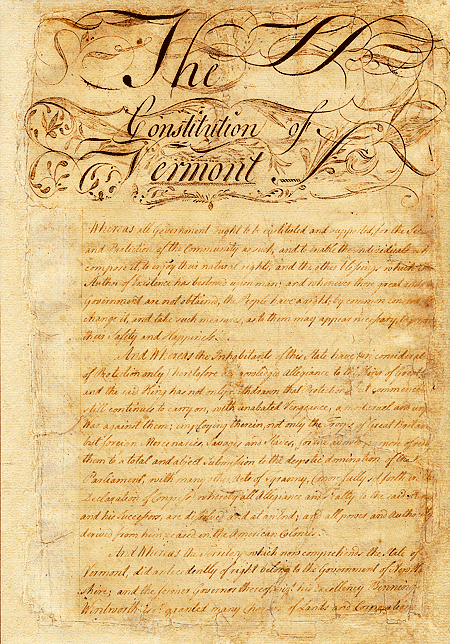

Vermont State Constitution, circa 1777.

|

Such an opportunity came on July 2, 1777. In response to abolitionists' calls across the colonies to end slavery, Vermont became the first colony to ban it outright. Not only did Vermont's legislature agree to abolish slavery entirely, it also moved to provide full voting rights for African American males. On November 25, 1858, Vermont would again underscore this commitment by ratifying a stronger anti-slavery law into its constitution.

Vermont's July 2, 1777 action was undoubtedly a historic event. The proclamation underscored the growing discontent many had with slavery and the slave trade, particularly in the colonies of the North where Quaker-led abolitionist movements were taking root.

Earlier, in 1774, New England-area colonies Rhode Island and Connecticut had outlawed overseas slave importation, but still allowed inter-colony slave trade.

Regardless of the good legal intentions of New England legislators, black Americans continued to be treated with disdain and cruelty in the North.

While Vermont, Rhode Island and Connecticut abolitionists achieved laudable goals, each state created legal strictures making it difficult for “free” blacks to find work, own property or even remain in the state.

Rhode Island, while legally ending slave importation from overseas, continued to have the highest number of slave auctions in the New England states. Additionally, Rhode Island's laws governing the treatment of African Americans — free or slave — were continually revised and updated and were among the harshest in the colonies.

If free blacks associated with slaves, both could and would be whipped. Anyone giving an African American a cup of hard cider was leveled with a heavy fine, whipped or both.

Vermont's July 1777 declaration was not entirely altruistic either. While it did set an independent tone from the 13 colonies, the declaration's wording was vague enough to let Vermont's already-established slavery practices continue.

The harshest treatment for free blacks in New England was found in Connecticut. Through a series of different legislative acts created before and after the Revolutionary War, it became nearly impossible for free African Americans to live in the state. For example, free blacks could not walk into a business without the proprietor's consent, nor could free blacks own property.

In fact, Connecticut lawmakers were so strident in their efforts to push blacks out of their state, the property law was rewritten to be retroactive. The few free African Americans who did own land were forced to void their titles and return property ownership to the town.

More often than not, New England emancipation declarations provided cover for more covert laws that ultimately sought to force African Americans into leaving their states. Whether free or not, black Americans clearly understood that their day-to-day welfare was dependent on their ability to both challenge and accommodate the racism they faced.

African Americans during this period were more often treated — at least physically — better than their kinsmen and women in the South. But they remained discriminated against, unwanted, and, at times, subjected to harsh treatment similar to that suffered by enslaved Africans in the South.

So, while it is important to note the intent of the Vermont legislature when it banned slavery — to send a message of independence from the original colonies — it is equally important to understand that the lives of free black men and women in Vermont and elsewhere in New England remained harsh and unfair.

|