Potawatomi (Prairie Band in Kansas) man's apron/breechcloth panel, ca. 1900,

NMAI 24/1996

George Godfrey (Citizen Potawatomi Nation) provides a blessing north of Rochester, Indiana, on September 15, 2006.

Photograph by Lyn Ward, Plymouth, Indiana.

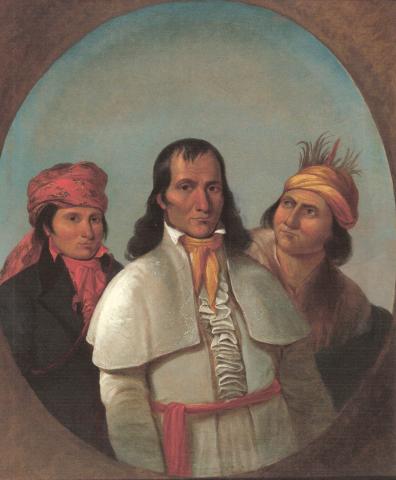

Three Potawatomi Chiefs, 1863-71. by George Winter, after 1837 sketches

Wisconsin Historical Society WHS-2975

Mesquawbuck (right) was a former war chief held in great respect. Naswakkay (middle) knew the treaties by memory and spoke for his people in negotiations. Iowa (left) was a younger man who tried to achieve influence by cooperating with the United States. He signed a fraudulent treaty in 1836.

Three Potawatomi Chiefs Visual Thinking Exercise

The new NMAI video, Nation to Nation: The "Indian Problem" focuses on Indian removal. As American power and population grew in the 1800's, the United States gradually rejected the main principle of treaty-making—that tribes were self-governing nations—and initiated policies that undermined tribal sovereignty.

Selected as the 2014 winner of the American Indian Youth Literature Award by the American Indian Library Association, How I Became a Ghost is a middle-grade level story about the forced relocation of the Choctaw people.

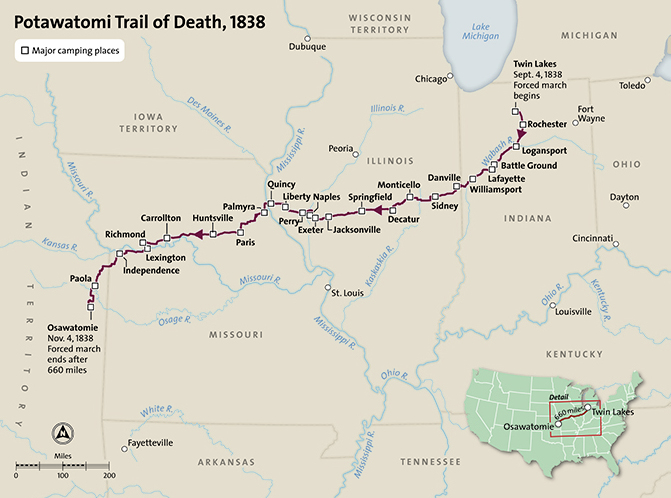

The town of Osawatomie, Kansas, was the end of the Trail of Death for the Potawatomi. Ironically, if you research the town name, you discover that it derives from the Osage and Potawatomi (which are both called local tribes, with no mention that the Potawatomi were forced there). Also, during a 1910 visit to Osawatomie, former President Teddy Roosevelt advocated for New Nationalism, a philosophy that promoted federal government protection for human welfare and property rights.

Walking the Qhapaq Ñan. Jujuy, Argentina, Photo by Axel E. Nielsen, 2005

The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire

This new bilingual exhibition, opening June 26, 2015, at NMAI-DC, explores the engineering genius of the Inka. It includes technologies that made building the road possible, the cosmology and political organization of the Inka world, and the legacy of the Inka Empire during the colonial period and today.

The Inka road network was 24,000 miles long and stretched from Colombia to Chile. |

|

“History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.” Maya Angelou

Many people know that American Indians were often unjustly dealt with by the U.S. government, but they often lack specific details. A commonly heard phrase is that “Treaties were all broken.” While this statement has a lot of truth, it doesn’t allow for a fuller dialogue about how land was taken from American Indians through enticement, threat, deception, force, and a new law formalizing the process -- the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which President Andrew Jackson pushed through Congress in his first year of office. Indian removal was not limited to what is typically taught in the classroom -- a few paragraphs about the five “civilized” tribes or the Trail of Tears. Removal was complex and controversial, even among non-Indians. The new exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian, Nation to Nation: Treaties between the United States and American Indians, and this newsletter help provide some details about the forced removal of the Chief Menominee band of the Potawatomi.

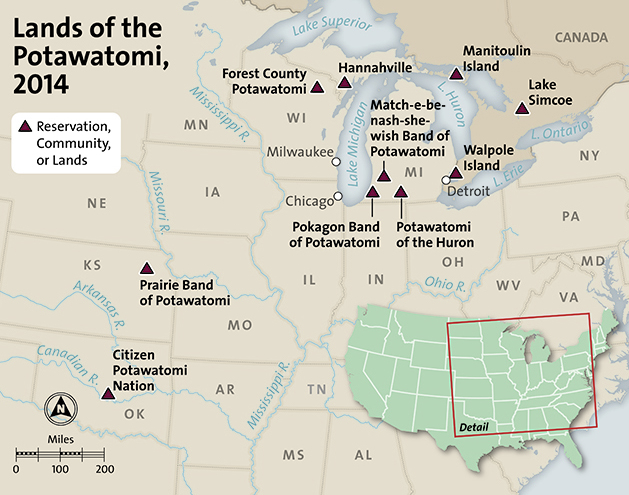

Collectively, the Potawatomi (People of the Small Prairie) signed more than 40 treaties to stay in their homes. But despite the promises made by the U.S. government, many Potawatomi people do not reside today in their traditional lands, the homes of their ancestors. A band of Potawatomi, under Chief Menominee, was forced from their homelands in Indiana, although Chief Menominee had not agreed to leave and did not sign the Treaty of Yellow River in 1836. Their removal was called the Trail of Death because 850 people were forced on a two-month walk to Osawatomie, Kansas. During the 660-mile walk, a typhoid epidemic struck, but the militia forced the sick to continue. Sadly, many people died.

How can we really understand what tribes endured while on the removal trails? They traveled by horse, wagon, or on foot, often prodded by bayonets. Sometimes the survivors arrived in the new lands promised to them without their family members who had died from disease or hunger along the way. Sometimes the new lands were already occupied by other removed Indian Nations that had been promised the same land. And yet while Indian tribes lost their homes and had to leave their ancestors behind, not all is lost.

Today, some removed communities have sought to more deeply understand the traditions tied to their homelands. Others have erected historic trails or highway markers, and conducted ceremonies to renew the spiritual ties to the lands where their ancestors reside. Although it has been difficult to maintain cultural practices inspired by their traditional lands, removed Indian Nations do continue to practice ceremonies and traditions in their new homelands, working together to persist and endure.

Niyaawe! (Thank you!)

Renée Gokey (Eastern Shawnee/Sac and Fox/Miami)

Education Extension Services

Potawatomi Trail of Death

On September 29, 2013, Kansas Governor Sam Brownback signed a proclamation recognizing the history and perseverance of the Potawatomi. Here he apologizes to a group of Potawatomi for the deaths, hardships and maltreatment their ancestors endured along the Trail of Death. Photograph by Shirley Willard. Read the proclamation here. On September 29, 2013, Kansas Governor Sam Brownback signed a proclamation recognizing the history and perseverance of the Potawatomi. Here he apologizes to a group of Potawatomi for the deaths, hardships and maltreatment their ancestors endured along the Trail of Death. Photograph by Shirley Willard. Read the proclamation here.

The Dakota Reconciliation Ride is a yearly horseback ride from the Lower Brule Indian Reservation in South Dakota to Mankato, Minnesota, in honor of the 38 executed Dakota. Photograph by John Cross, 2010. Mankato Free Press

In the late summer of 1862, a war raged across southern Minnesota between Dakota akicitas (warriors) and the U.S. military and immigrant settlers. In the end, hundreds were dead and thousands more would lose their homes forever. On December 26, 1862, 38 Dakota men were hung in Mankato, Minnesota, by order of President Abraham Lincoln. This remains the largest mass execution in U.S. history. The bloodshed of 1862 and its aftermath left deep wounds that have yet to heal.

This exhibition of 12 panels exploring the causes, voices, events, and long-lasting consequences of the conflict was produced by students at Gustavus Adolphus College in conjunction with the Nicollet County Historical Society.

Teacher Resources from the MN Historical Society

The Past Is Alive Within Us: The U.S.-Dakota Conflict

Dakota 38 Film

Facing History and Ourselves: Taking a Stand on Controversial Issues

|