|

Yup'ik girl wearing a plaid dress, ca. 1935-1937. Alaska. L02703

Eskimo has been used in the past to refer to Yup'ik and Inuit peoples. However, its origin was not from the peoples it refers to and is considered insulting, particularly in Canada and Greenland.

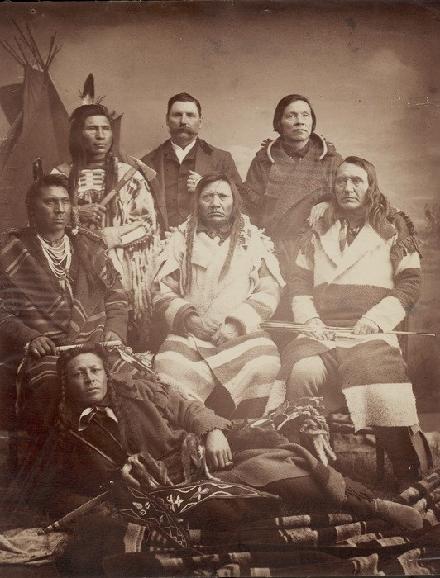

Salish delegation posing in front of a backdrop and a prop tipi, 1884. Front row: Tshamaxan. Middle row, left to right: Kal-Psuaci, Chief Slmqexe, Kut-Somxe (The Grizzly Bear Far Away). Back row, left to right: Teet-Cst, Peter Ronan (?) (Indian agent), Tcinkusui. Washington, DC. P03583

Salish people were historically misidentified as Flathead, which was incorrect, as they did not practice head flattening, which was practiced by some indigenous groups of the Americas and other cultures around the world.

SHOULD I SAY TRIBE OR NATION?

Tribe, nation, community, pueblo, rancheria, village, band--American Indian people describe their own cultures and the places they come from in many ways. Often, the words tribe and nation are used interchangeably, but for many Native people they can hold very different meanings.

WHY DO MANY TRIBES HAVE MORE THAN ONE NAME?

When Europeans arrived in the Americas, they rarely used a particular Indian nation's own name, and often used inaccurate pronunciations of those tribal names or they named the tribes using their own European terms.

Young poets from First Peoples Fund's Dances with Words, based on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, were in Washing-ton, DC, to compete at the 19th annual Brave New Voices International Spoken Word Poetry Festival in July 2016. The youth were one of 60 teams participating in workshops and open conversations, and competing with their poetry during the weeklong festival. Read this poem from Marcus Ruff, 18 (Oglala / Cheyenne River Sioux) from Allen, South Dakota, and Cetan Ducheneaux, 16 (Cheyenne River Sioux / Cherokee Nation) from Kyle, South Dakota. Marcus and Cetan both attend Red Cloud Indian School.

Rainbow at Red Shirt Table, spring 2015. Photo by Brandie Macdonald (Chickasaw/Choctaw), First Peoples Fund

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Happy National Arts Education Week September 11-17, 2016!

There is a new Craft in America episode titled "Teachers" that opens with an important story of

Navajo weaving, featuring fifth-generation weavers Barbara Teller Ornelas and Lynda Teller Pete.

"Teachers" premieres on PBS on September 15th at 8 p.m. as part of its "Spotlight Education Week" --- a special week of prime-time programming that examines challenges facing today¹s students and America's education system. See the Teachers 1 min preview here

and utilize this Education Guide that explores assimilation and advocacy.

All episodes are available for free at craftinamerica.org.

On August 15, 2016, two of NMAI's local teacher advisors, Deborah Bradby-Lytle and Dadre Blake, enjoyed a behind-the-scenes visit to NMAI's collections, where more than 800,000 Native American objects are housed at the Cultural Resource Center in Suitland, MD. Our work with teacher advisors allows us opportunities to find expanded ways to engage classroom teachers in Native American topics and content.

"It is amazing to see the science and thought that goes into each item or object and the role it played/plays in the lives of Native peoples. Seeing the buffalo bone sled, a kayak made from the skin of seals, and the duck feather parka reiterated the fact that very little went to waste and that Native Americans took great care to use as much of a natural resource as possible. There has to be a way to share this wealth of history to help demystify the Native culture."

---Dadre Blake

|

|

Welcome back to the classroom!

As a teacher, have you wondered the answer to the question "What term should I use: Native American or American Indian?" Our goal is to provide a better understanding of the diverse people, culture, traditions, and languages of the 567 federally recognized tribes within the United States. But often, the best start is with what to collectively call America's first people. Although the terms Native American and American Indian are often used interchangeably, many Native people have individual preferences on how they would like to be addressed. When meeting or referring to a Native person, we encourage you to ask what that specific person prefers. It's often their specific tribal nation or community. Interestingly, many Natives, when introduced to another Native, simply ask, “What tribe are you?”

The term Native is often used to officially and unofficially describe indigenous peoples from the United States (Native Americans, Native Hawaiians, Alaska Natives), but it can also serve as a specific descriptor (Native people, Native lands, Native traditions, etc.). According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), all Native peoples of North, Central, and South America are defined as Native Americans. The BIA also defines Native persons of the continental United States and the tribes of Alaska as American Indians and Alaska Natives, or AI/AN, respectively.

There are also several terms used to refer to the Native peoples to the north and south of the United States. In Canada, people refer to themselves as First Nations or aboriginal. Also, there is a specific name for each First Nation community, such as the Swan Lake First Nation in Manitoba. In Mexico, Central America, and South America, indigenous cultures do not like to use the Spanish or Portuguese words for Indian or tribe, since the direct translations carry negative meanings. As a result, most Native people in these areas use the words indígenas (“indigenous people” or “indigenous”) and communidad (“community”) to describe who they are or where they come from.

We also wanted to give you some history for our name, the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). Many of our visitors mistakenly believe this name validates that the term Native American should not be used. Instead, our name pays tribute to the beginnings of the National Museum of the American Indian. This year, NMAI celebrates the 100th anniversary of our predecessor, the Museum of the American Indian (MAI), which came into existence because of George Gustav Heye (1874-1957) and the impressive array of American Indian objects amassed for the museum he founded in 1916 in New York City. Explore this issue to learn more about the history of NMAI's rich collections and find some ways to teach with objects in your classroom.

Niyaawe! (Thank you!)

Renée Gokey (Eastern Shawnee/Sac and Fox/Miami)

Education Extension Services

Mr. and Mrs. (Thea) George Gustav Heye in front of the Museum of the American Indian/Heye Foundation, 155th and Broadway, New York, 1917. Photographer unknown, National Museum of the American Indian P11582

George and Thea Heye with Wey-hu-si-wa (Governor of Zuni Pueblo) and Lorenzo Chavez (Zuni) in front the Museum of the American Indian in 1923. Photographer unknown N08130

Vistas and Dreams: Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the Founding of the Museum of the American Indian

A special symposium at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York on Saturday, September 17, will mark the 100th anniversary of its predecessor institution—the Museum of the American Indian. Fascinated by American Indian cultures, George Gustav Heye (1874-1957) dreamed of founding a hemispheric American Indian museum to serve students of anthropology and the people of New York.

NMAI-NY Saturday, September 17, 2016, 2:00-5:30 p.m.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Maya Creativity and Cultural Milieu!

Celebrate Hispanic Heritage month with marimba music and hands-on activities such as a community mural, cardboard model skateboards with Maya calendar symbols and animal-symbol pendants by Indigenous Design Collective at the festival!

Guatemalan Maya youth and weavers representing organizations Unlocking Silent Histories and the Maya Traditions Foundation, will share their Maya identities, illustrating their resilience, knowledge, and unique traditions demonstrated through documentaries and traditional backstrap weaving.

NMAI-DC Friday & Saturday, September 16 & 17, 2016, 10:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m.

Sunday, September 18, 2016, 10:00 a.m.-2:00 p.m.

Glimpses of

100 Years of the

Museum’s History

History of NMAI's Collections

Significance of NMAI's Collections

Moving NMAI's Collections

Why should I teach with objects in my classroom?

- Objects strengthen cultural and language connections. Using objects helps deepen critical thinking, particularly in subjects such as history and social studies, even if students have limited English vocabulary.

Read this article to learn more about using objects with English language learners.

- Objects are interesting. They go beyond facts and figures to excite student learning.

- Objects are accessible. They aren't as age-specific as text and can add more inclusive approaches to different learning styles and diverse students.

- Objects are real life. Kids can see themselves in different objects and make powerful connections between history and life today.

- Objects hold cultural knowledge. In some Native communities, objects can reveal forgotten techniques that are being studied and reclaimed again. They might exemplify ingenuity and provide concrete evidence of rich Native science practices well before contact with Europeans.

- Objects tell stories. They are imbued with spirit and life when they are made and help to maintain cultural values and connections. They hold powerful memories that can be felt.

Use this graphic organizer to practice describing and inferring information about an NMAI object. Here's an example. Use the object images and questions in this guide to practice critical thinking skills and develop your students' visual literacy!

Yup'ik Girl's parka, ca. 1890-1905, Mamterilleq, Alaska. Duck skin/skins, wolf skin/fur, squirrel skin/fur (ground squirrel), duck wing, sinew 1/6826

This girl’s parka is made from duck feathers that would help keep a child warm and dry. Wolf fur, often around the edges of the hood, hem and cuffs of a parka, protects the face because irregular hair lengths help break the wind and wolf (or sometimes, dog or wolverine) fur sheds ice and frost. A great example of Yup’ik science and knowledge!

|